A New Study Shows ChatGPT is Dramatically Weakening Our Brains

On the perils of ultra-processed content, and how you can build and protect your cognitive fitness

A first-of-a-kind study out of MIT shows that an over-reliance on tools like chatGPT leads to a massive decline in cognitive function. The results are important, and carry practical implications.

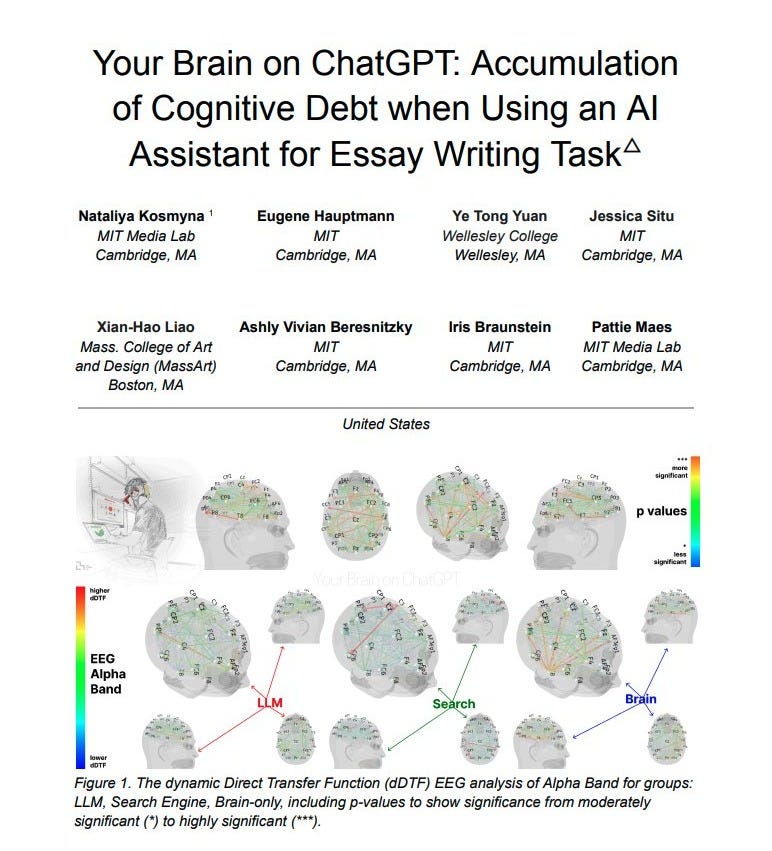

For four months, researchers evaluated what happened to people who used ChatGPT to complete writing assignments for them, versus those who did not. The headline result: “LLM users consistently underperformed at neural, linguistic, and behavioral levels.”

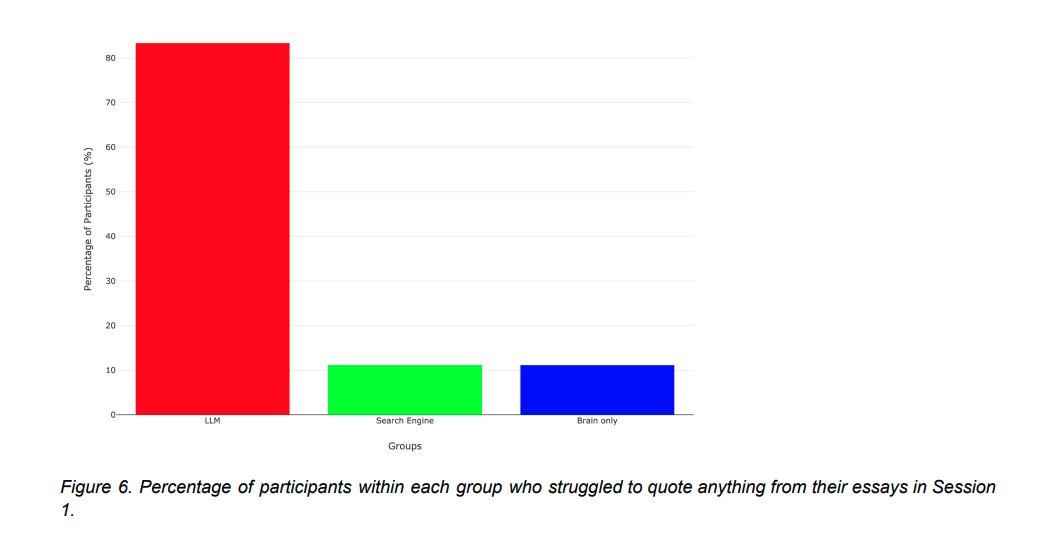

Over 80% of ChatGPT users couldn’t quote anything from work they’d just done. When researchers read the essays written by AI, they used the following words to describe them:

“Soulless.”

“Empty.”

“Standard and typical.”

“Lacking individuality.”

The essays written by AI were scored as flat and homogenized. The writing was punchy, but quickly became boring; it all had the same synthetic feel. Perhaps most notably, LLM users saw a 47% reduction in brain connectivity compared to people who did not rely on ChatGPT to write for them.

These results may seem shocking, but they also make sense: if you are outsourcing your thinking to a machine, by definition, you don’t need to think, and you certainly don’t need to make creative and associative connections. A hallmark of deep thinking is that it relies on different parts of the brain working together. When you outsource writing to AI, you negate this process.

The case for cognitive fitness

As I was reading this study, I kept thinking that much like your physical health deteriorates if your diet includes too many highly-processed foods, your cognitive health deteriorates if your information diet, both what you produce and consume, includes too much highly-processed content.

Another useful metaphor for thinking about AI is fitness. If you outsource all your physicality to technology then your physical fitness will decline, and fast. If you outsource all your thinking to technology then your cognitive fitness will decline fast too. When researchers forced heavy ChatGPT users to write without AI, not only did they struggle, but their writing was worse than people who had never used ChatGPT.

Writing in particular provides a heavy cognitive strain. The author and computer scientist Cal Newport interviewed dozens of college students who were heavy AI users. They weren’t using the tools to plagiarize; they were using the tools to write first drafts, provide structure for their work, and help them form ideas. In other words, they were using AI to outsource the hard parts of writing, like “a brain hack used to make the act of writing feel less difficult,” explains Newport.

But a big part of the reason to write is because it is difficult. Writing well is a proxy for thinking well. Using AI to write for you is like going to the gym, but instead of lifting the weights yourself, you bring an apparatus to do the work. You may lift plenty of weight this way, but you yourself aren’t getting stronger. Over time, your muscles will atrophy. Perhaps you become great at configuring and programming the apparatus, but that is a very different skill than a squat or deadlift.

At the same time, it’s pretty great that we have forklifts for moving massive loads at warehouses. A world in which humans have to do all this work without assistance probably would not be better, and there are many ways in which it could be worse. Using AI to sequence DNA and find patterns in massive data sets could help develop therapeutics for diseases like cancer. That is a great use of a forklift. Same tool, different tradeoffs. Discernment is everything.

Efficiency, but at a steep cognitive debt

Relying on AI is efficient. The study participants who “wrote” with AI were much faster, because of course. But what they gained in efficiency they lost tenfold in quality, humanity, and long-term cognitive fitness.

The MIT researchers coined the term “cognitive debt” to explain this tradeoff: what you gain in efficiency now, you pay for later.

These findings are particularly worrisome for young people.

We know the human brain is most plastic until the age of 25. If youth become reliant on AI, they may never learn to think for themselves. Allowing AI in schools without any guardrails would be running a massive experiment on an entire generation in real-time.

Where to go from here?

There is no putting this technology back in the box, but we’ve got to be thoughtful about how we use it and set constraints and rules for ourselves. Occasionally I eat highly processed foods. I’m still healthy and fit, but I’d never make them the centerpiece of my diet. I still drive a car, and I am grateful for vehicular transportation. But I also make sure to get my steps in. Though I could outsource nearly all my physicality to technologies, I don’t. Because I know that whatever ease and convenience I’d feel in the short-term, I’d be trading for problems down the road. The same is true for the production and consumption of highly processed content.

The writer Derek Thompson (who just joined Substack) has hypothesized that tools like ChatGPT “can be great curiosity enhancers, but, if used to replace production, the results may be terrible.” Or maybe AI automation processes will be a boon for administrative and busy work, but a curse when used for higher-level thinking. I truly don’t think anyone knows.

The last digital technological breakthrough was the smartphone. It’s many benefits are undeniable. But, so, too, are some of its costs: for example, those who use regularly use map apps see declines in their innate navigation ability. The rise of the phone-based childhood is strongly associated with a youth mental health crisis, and a large regret of the parents of Gen Z youth is that they gave their kids smartphones too early. (And kids themselves regret their own addictive smartphone use, too.)

The point is that we shouldn’t always just go with the flow in the face of new technologies. At the very least, we owe it to ourselves (and to our children) to identify potential harms and do what we can to reduce them. Losing the ability to navigate without a map is one thing, but losing the ability to think for ourselves is another entirely.

AI is still in its infancy. Its impact on our future—both individually and collectively—depends on our ability to use it thoughtfully. The problem is the more we use it to replace thinking, the less thoughtful we become. Your thinking will deteriorate if you rely on shortcuts. The muscles you have built will atrophy if you outsource them to servers. None of this is to say you should shun AI. But you should be deliberate about why, when, and how you use it—and what you get in return versus what you give up.

Thinking for ourselves is a central feature of our humanity. It’s best we don’t take it for granted.

The only thing the movie Wall-E got wrong was how quickly the laziness would come. In our AI-driven, automated future, being fully human will be an act of resistance ✊

I work in e-commerce and I hear “just ChatGPT it” way too often at work. I also feel like when we do have successful breakthroughs, no one can explain why because ChatGPT was doing to hard work. I am also the oldest person in the office so if I say something they just shake their heads and say I’m too old school. I’ll just keep flexing my cognitive muscles as long as I can get away with it!